How Sharding Works

[TOC]

This is a continuation of my last post, why I love databases

Your application suddenly becomes popular. Traffic and data is starting to grow, and your database gets more overloaded every day. People on the internet tell you to scale your database by sharding, but you don’t really know what it means. You start doing some research, and run into this post.

Welcome!

1. What is sharding?

Sharding is a method of splitting and storing a single logical dataset in multiple databases. By distributing the data among multiple machines, a cluster of database systems can store larger dataset and handle additional requests. Sharding is necessary if a dataset is too large to be stored in a single database. Moreover, many sharding strategies allow additional machines to be added. Sharding allows a database cluster to scale along with its data and traffic growth.

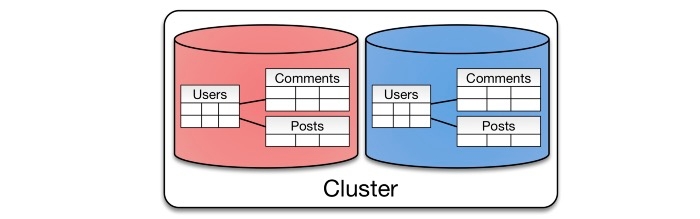

Sharding is also referred as horizontal partitioning. The distinction of horizontal vs vertical comes from the traditional tabular view of a database. A database can be split vertically — storing different tables & columns in a separate database, or horizontally — storing rows of a same table in multiple database nodes.

An illustrated example of vertical and horizontal partitioning

Vertical partitioning is very domain specific. You draw a logical split within your application data, storing them in different databases. It is almost always implemented at the application level — a piece of code routing reads and writes to a designated database.

In contrast, sharding splits a homogeneous type of data into multiple databases. You can see that such an algorithm is easily generalizable. That’s why sharding can be implemented at either the application or database level. In many databases, sharding is a first-class concept, and the database knows how to store and retrieve data within a cluster. Almost all modern databases are natively sharded. Cassandra, HBase, HDFS, and MongoDB are popular distributed databases. Notable examples of non-sharded modern databases are Sqlite, Redis (spec in progress), Memcached, and Zookeeper.

There exist various strategies to distribute data into multiple databases. Each strategy has pros and cons depending on various assumptions a strategy makes. It is crucial to understand these assumptions and limitations. Operations may need to search through many databases to find the requested data. These are called cross-partition operations and they tend to be inefficient. Hotspots are another common problem — having uneven distribution of data and operations. Hotspots largely counteract the benefits of sharding.

2. Before you start: you may not need to shard!

Sharding adds additional programming and operational complexity to your application. You lose the convenience of accessing the application’s data in a single location. Managing multiple servers adds operational challenges. Before you begin, see whether sharding can be avoided or deferred.

Get a more expensive machine. Storage capacity is growing at the speed of Moore’s law. From Amazon, you can get a server with 6.4 TB of SDD, 244 GB of RAM and 32 cores. Even in 2013, Stack Overflow runs on a single MS SQL server. (Some may argue that splitting Stack Overflow and Stack Exchange is a form of sharding)

If your application is bound by read performance, you can add caches or database replicas. They provide additional read capacity without heavily modifying your application.

Vertically partition by functionality. Binary blobs tend to occupy large amounts of space and are isolated within your application. Storing files in S3 can reduce storage burden. Other functionalities such as full text search, tagging, and analytics are best done by separate databases.

Not everything may need to be sharded. Often times, only few tables occupy a majority of the disk space. Very little is gained by sharding small tables with hundreds of rows. Focus on the large tables.

3. Driving Principles

To compare the pros and cons of each sharding strategy, I’ll use the following principles.

How the data is read — Databases are used to store and retrieve data. If we don’t need to read data at all, we can simply write it to /dev/null. If we only need to batch process the data once in a while, we can append to a single file and periodically scan through them. Data retrieval requirements (or lack thereof) heavily influence the sharding strategy.

How the data is distributed — Once you have a cluster of machines acting together, it is important to ensure that data and work is evenly distributed. Uneven load causes storage and performance hotspots. Some databases redistribute data dynamically, while others expect clients to evenly distribute and access data.

Once sharding is employed, redistributing data is an important problem. Once your database is sharded, it is likely that the data is growing rapidly. Adding an additional node becomes a regular routine. It may require changes in configuration and moving large amounts of data between nodes. It adds both performance and operational burden.

4. Common Definitions

Many databases have their own terminologies. The following terminologies are used throughout to describe different algorithms.

Shard or Partition Key is a portion of primary key which determines how data should be distributed. A partition key allows you to retrieve and modify data efficiently by routing operations to the correct database. Entries with the same partition key are stored in the same node. A logical shard is a collection of data sharing the same partition key. A database node, sometimes referred as a physical shard, contains multiple logical shards.

5. Case 1 — Algorithmic Sharding

One way to categorize sharding is algorithmic versus dynamic. In algorithmic sharding, the client can determine a given partition’s database without any help. In dynamic sharding, a separate locator service tracks the partitions amongst the nodes.

Algorithmically sharded databases use a sharding function (partition_key) -> database_id to locate data. A simple sharding function may be “hash(key) % NUM_DB”.

Reads are performed within a single database as long as a partition key is given. Queries without a partition key require searching every database node. Non-partitioned queries do not scale with respect to the size of cluster, thus they are discouraged.

Algorithmic sharding distributes data by its sharding function only. It doesn’t consider the payload size or space utilization. To uniformly distribute data, each partition should be similarly sized. Fine grained partitions reduce hotspots — a single database will contain many partitions, and the sum of data between databases is statistically likely to be similar. For this reason, algorithmic sharding is suitable for key-value databases with homogeneous values.

Resharding data can be challenging. It requires updating the sharding function and moving data around the cluster. Doing both at the same time while maintaining consistency and availability is hard. Clever choice of sharding function can reduce the amount of transferred data. Consistent Hashing is such an algorithm.

Examples of such system include Memcached. Memcached is not sharded on its own, but expects client libraries to distribute data within a cluster. Such logic is fairly easy to implement at the application level.

6. Case 2— Dynamic Sharding

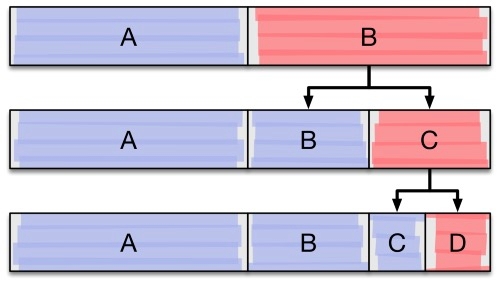

A dynamic sharding scheme using range based partitioning.

In dynamic sharding, an external locator service determines the location of entries. It can be implemented in multiple ways. If the cardinality of partition keys is relatively low, the locator can be assigned per individual key. Otherwise, a single locator can address a range of partition keys.

To read and write data, clients need to consult the locator service first. Operation by primary key becomes fairly trivial. Other queries also become efficient depending on the structure of locators. In the example of range-based partition keys, range queries are efficient because the locator service reduces the number of candidate databases. Queries without a partition key will need to search all databases.

Dynamic sharding is more resilient to nonuniform distribution of data. Locators can be created, split, and reassigned to redistribute data. However, relocation of data and update of locators need to be done in unison. This process has many corner cases with a lot of interesting theoretical, operational, and implementational challenges.

The locator service becomes a single point of contention and failure. Every database operation needs to access it, thus performance and availability are a must. However, locators cannot be cached or replicated simply. Out of date locators will route operations to incorrect databases. Misrouted writes are especially bad — they become undiscoverable after the routing issue is resolved.

Since the effect of misrouted traffic is so devastating, many systems opt for a high consistency solution. Consensus algorithms and synchronous replications are used to store this data. Fortunately, locator data tends to be small, so computational costs associated with such a heavyweight solution tends to be low.

Due to its robustness, dynamic sharding is used in many popular databases. HDFS uses a Name Node to store filesystem metadata. Unfortunately, the name node is a single point of failure in HDFS. Apache HBase splits row keys into ranges. The range server is responsible for storing multiple regions. Region information is stored in Zookeeper to ensure consistency and redundancy. In MongoDB, the ConfigServer stores the sharding information, and mongos performs the query routing. ConfigServer uses synchronous replication to ensure consistency. When a config server loses redundancy, it goes into read-only mode for safety. Normal database operations are unaffected, but shards cannot be created or moved.

7. Case 3 — Entity Groups

Entity Groups partitions all related tables together

Previous examples are geared towards key-value operations. However, many databases have more expressive querying and manipulation capabilities. Traditional RDBMS features such as joins, indexes and transactions reduce complexity for an application.

The concept of entity groups is very simple. Store related entities in the same partition to provide additional capabilities within a single partition. Specifically:

Queries within a single physical shard are efficient.

Stronger consistency semantics can be achieved within a shard.

This is a popular approach to shard a relational database. In a typical web application data is naturally isolated per user. Partitioning by user gives scalability of sharding while retaining most of its flexibility. It normally starts off as a simple company-specific solution, where resharding operations are done manually by developers. Mature solutions like Youtube’s Vitess and Tumblr’s Jetpants can automate most operational tasks.

Queries spanning multiple partitions typically have looser consistency guarantees than a single partition query. They also tend to be inefficient, so such queries should be done sparingly.

However, a particular cross-partition query may be required frequently and efficiently. In this case, data needs to be stored in multiple partitions to support efficient reads. For example, chat messages between two users may be stored twice — partitioned by both senders and recipients. All messages sent or received by a given user are stored in a single partition. In general, many-to-many relationships between partitions may need to be duplicated.

Entity groups can be implemented either algorithmically or dynamically. They are usually implemented dynamically since the total size per group can vary greatly. The same caveats for updating locators and moving data around applies here. Instead of individual tables, an entire entity group needs to be moved together.

Other than sharded RDBMS solutions, Google Megastore is an example of such a system. Megastore is publicly exposed via Google App Engine’s Datastore API.

8. Case 4 — Hierarchical keys & Column-Oriented Databases

Column-oriented databases partition its data by row keys.

Column-oriented databases are an extension of key-value stores. They add expressiveness of entity groups with a hierarchical primary key. A primary key is composed of a pair (row key, column key). Entries with the same partition key are stored together. Range queries on columns limited to a single partition are efficient. That’s why a column key is referred as a range key in DynamoDB.

This model has been popular since mid 2000s. The restriction given by hierarchical keys allows databases to implement data-agnostic sharding mechanisms and efficient storage engines. Meanwhile, hierarchical keys are expressive enough to represent sophisticated relationships. Column-oriented databases can model a problem such as time series efficiently.

Column-oriented databases can be sharded either algorithmically or dynamically. With small and numerous small partitions, they haveconstraints similarto key-value stores. Otherwise, dynamic sharding is more suitable.

The term column database is losing popularity. Both HBase and Cassandra once marketed themselves as column databases, but not anymore. If I need to categorize these systems today, I would call them hierarchical key-value stores, since this is the most distinctive characteristic between them.

Originally published in 2005, Google BigTable popularized column-oriented databases amongst the public. Apache HBase is a BigTable-like database implemented on top of Hadoop ecosystem. Apache Cassandra previously described itself as a column database — entries were stored in column families with row and column keys. CQL3, the latest API for Cassandra, presents a flattened data model — (partition key, column key) is simply a composite primary key. Amazon’s Dynamo popularized highly available databases. Amazon DynamoDB is a platform-as-a-service offering of Dynamo. DynamoDB uses (hash key, range key) as its primary key.

9. Understanding the pitfalls

Many caveats are discussed above. However, there are other common issues to watch out for with many strategies.

A logical shard (data sharing the same partition key) must fit in a single node. This is the most important assumption, and is the hardest to change in future. A logical shard is an atomic unit of storage and cannot span across multiple nodes. In such a situation, the database cluster is effectively out of space. Having finer partitions mitigates this problem, but it adds complexity to both database and application. The cluster needs to manage additional partitions and the application may issue additional cross-partition operations.

Many web applications shard data by user. This may become problematic over time, as the application accumulates power users with a large amount of data. For example, an email service may have users with terabytes of email. To accommodate this, a single user’s data is split into partitions. This migration is usually very challenging as it invalidates many core assumptions on the underlying data model.

Illustration of a hotspot at the end of partition range even after numerous shard splits.

Even though dynamic sharding is more resilient to unbalanced data, an unexpected workload can reduce its effectiveness. In a range-partitioned sharding scheme, inserting data in partition key order creates hot spots. Only the last range will receive inserts. This partition range will split as it becomes large. However, out of the split ranges, only the latest range will receive additional writes. The write throughput of a cluster is effectively reduced to a single node. MongoDB, HBase, and Google Datastore discourages this.

In the case of dynamic sharding, it is bad to have a large number of locators. Since the locators are frequently accessed, they are normally served directly from RAM. HDFS’s Name Node needs at least 150 bytes of memory per file for its metadata, thus storing a large number of files is prohibitive. Many databases allocate a fixed amount of resources per partition range. HBase recommends about 20~200 regions per server.

10. Concluding Remarks

There are many topics closely related to sharding not covered here. Replication is a crucial concept in distributed databases to ensure durability and availability. Replication can be performed agnostic to sharding or tightly coupled to the sharding strategies.

The details behind data redistribution are important. As previously mentioned, ensuring both the data and locators are in sync while the data is being moved is a hard problem. Many techniques make a tradeoff between consistency, availability, and performance. For example, HBase’s region splitting is a complex multi-step process. To make it worse, a brief downtime is required during a region split.

None of this is magic. Everything follows logically once you consider how the data is stored and retrieved. Cross-partition queries are inefficient, and many sharding schemes attempt to minimize the number of cross-partition operations. On the other hand, partitions need to be granular enough to evenly distribute the load amongst nodes. Finding the right balance can be tricky. Of course, the best solution in software engineering is avoiding the problem altogether. As stated before, there are many successful websites operating without sharding. See if you can defer or avoid the problem altogether.

Happy databasing!

最后更新于